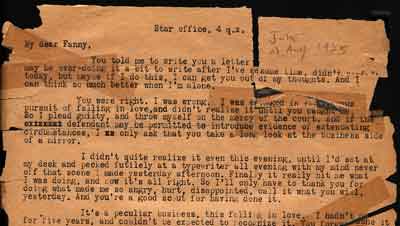

I held a mystery in my hand: two sheets of aged paper, browned by the passage of some seventy years, bits and pieces flaking off in my fingers, scattering on the carpet. “Star office” was typed at the top of the first page, and the two sheets were covered with closely typed lines:

| You were right. I was wrong. I was engaged in the furious pursuit of falling in love. . . . Let’s begin at the apparent beginning — the Oracle trip and the dance. |

The width of the paper told me it had been trimmed from the big sheets that in the first half of the past century were stacked in newspaper composing rooms for pulling proofs from the big metal page forms filled with type.

The creases in the two typed pages told me that the paper had once been folded inside a very small envelope; the transparent mending tape that kept them from falling apart over the years indicated that this was a very special letter to the person who had received it. There was a penciled date: “July or Aug. 1925.”

The person who had received it: That was Fanny Strassman. I met her once when I stopped off in Manhattan on my way home from Europe. She was then an effervescent New York literary agent midway through her sixties. But that was some four decades after she had received the mysterious letter.

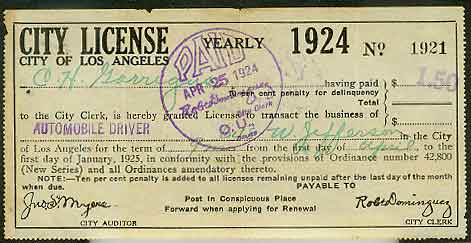

The person who wrote it: That was my father, or at any rate, the man who would become my father. He signed it: “Brick”; That was his nickname; his legal name was Charles Harris Garrigues.

| Star office My dear Fanny, You told me to write you a letter some time, didn’t you? It may be overdoing it a bit to write after I’ve seen you twice today, but maybe if I do this, I can get you out of my thoughts. You were right. I was wrong. I was engaged in the furious pursuit of falling in love, and didn’t realize it until you caught me. So I plead guilty, and throw myself on the mercy of the court. And if the defendant may be permitted to introduce evidence of extenuating circumstances, I only ask that you take a long look at the business side of a mirror. I didn’t quite realize it even this evening, until I’d sat at my desk and pecked futilely at a typewriter all evening with my mind never off that scene I made yesterday afternoon. Finally what I was doing really hit me, and now it’s all right. So I’ll only have to thank you for doing what made me so angry, hurt, disappointed, call it what you will, yesterday. And you’re a good scout for having done it. It’s a peculiar business, this falling in love. I hadn’t done it for five years, and couldn’t be expected to realize it. You forget all about your own ego, your own ideas; the whole universe is out of focus. You only want to do that which somebody wants to you do, or thinks she wants you to do, or you think she wants you to do. When all the time you mustn’t do that at all. It’s a form of youth that man should put off when he becomes of age, and I feel sure tonight that I won’t have any inclination to do it again. Since I’m doing this chiefly to get it out of my system, lets begin at the apparent beginning — the Oracle trip and the dance. There can be only three propositions. If the first two are incorrect, the third must be right. (Weininger says women cannot reason. We shall see.) Proposition 1. — Conceding that we are “playmates” and there can be no thought of jealousy between us, except insofar as one of us departs from this status and seeks to become something more. That I might do that and become jealous of you is conceivable, but that you might is impossible. We agree on that. Therefore, it could not have been your dislike of the thought of Dickie spending the day with me that caused the trouble. That, I believe, was one of your points, and that is clearly untenable. Proposition 2. — Conceding that we are “playmates,” and further conceding that Dickie is the only sort of girl I’d go with, and again conceding that I’m perfectly honest with her, as I have been with you, there can be no thought of Dickie feeling badly if you went to Oracle. Only Proposition 3 remains: The realization that I was falling in love with you with an accelerating velocity. Can you blame me that when I’d been stopped in this process and brought back to earth I was a bit stunned? It took me some time to get used to it — first to the realization that I had fallen love, and second to the conviction that I must fall out at once. So I wandered around dazed, and finally came down here to write stories backwards and things like that. So that’s over. Whatever hurt there is — and love always hurts — can be patched up overnight, and I’ll be as good as ever in the morning. And I feel sure that if I ever find myself loving you again, I’ll recognize the symptoms and quit — cold. That’s the only thing to do. Before I knew I mustn’t, daren’t love you, but I unconsciously wanted to. Now that I don’t want to I’d like to come up this afternoon as we’d planned, partly to see you, partly to look at all the bad things there must be about you if I could only have seen them before, and partly to appease my vanity by letting you know that I’m not always so foolish as I have been — even though I may be utterly inconsequential. This is a hell of a letter — typewriter, copy paper, and subject matter. To you, perhaps, who have not been affected by the catacclasm (or however you spell it) of the last two weeks, it probably seems foolish to waste so much time writing on a (to you) inconsequential subject. It was only a short time, and can’t seem to matter very much. Yet I had started to rebuild myself — all unconsciously — according to your wishes; it was brief, but the most monumental thing that had happened to me in years. If I had a confidante to whom I could talk, I should not have troubled you with this, but I still feel that I can confide in you as I can to no one else, as I can hardly confide in myself. So you’ll forgive me if I’ve taken your time with all this. I’ll see you, if I may, at two? And I can assure you I’ll be my own self again, a self that doesn’t fall in love, and which, if you don’t like, you can lead ungently to the door. May I sign myself Your playmate, Brick (But oh, lady, lady, how wonderful it would have been if I’d dared to love you as much as I wanted to.) |

•

|

•