Los Angeles in the Jazz Age, city of dreams, city of romance. Sunshine every day. In every back yard, a swimming pool. Warm, sandy beaches. The women were all beautiful and the men handsome. The waitress who served your morning coffee knew someone who had a friend who was going to get her in the movies.

Ah, the motion picture, that illusionist of fantasy. Say, wasn’t that Ramon Navarro speeding down Sunset Boulevard in his white roadster? Didn’t you just see Gloria Swanson float into the Garden of Allah hotel with her entourage? That was the image.

The reality:

Jobs. Lots of them. A six-day week, pay every Saturday morning. Construction. Hard work. Roads being laid, houses built. A new City Hall breaking the twelve-story earthquake limit and soaring to twenty-six floors. Oil wells being drilled. Tough, dirty work there.

In the southeast county, the new $7 million Samson Tire and Rubber plant was going up, its faux-Assyrian ramparts glistening in the sunshine. Orange groves, lemon groves, walnut orchards, olives being planted or harvested. Jobs. Money. Leave where you are and come to L. A. Gloria Swanson? Just an image on a glass-beaded screen on a Saturday night.

During the Twenties, L. A.’s population climbed from half a million to more than 1.2 million. Hardly anybody was a native — to be “born here” was a badge of distinction. In number of people, it came just behind New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit. And it was gaining on Detroit.

By area, it was the largest: its politicians controlled an enormous swath of territory, from the vast agricultural fields and orchards of the San Fernando Valley on the north, where the water poured in through the aqueduct from the Owens Valley, to the bustling ports of San Pedro and Wilmington, where the booze poured in from Mexico and Canada.

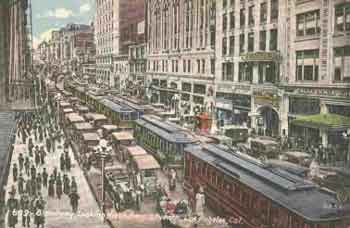

The newcomers found a city laced with streetcar lines and interurban electric railroads, but one that still had miles upon miles of open fields and unpaved drainage ditches. The business core was that stretch of five or six blocks running south on Broadway from First Street.

The place to look for a job was in the classified columns of the Los Angeles Times, a paper filled with publisher Harry Chandler’s scorn for labor unions and other “disruptive” social forces.

There were other dailies, too — the Herald and the Express (both owned by William Randolph Hearst), the Hollywood Citizen-News (Harlan Palmer’s paper), the Santa Monica Outlook, Pasadena Star-News, Beverly Hills Citizen, Inglewood Daily News, and on and on. Every little town seemed to have one.

The brash kid in a new building on 11th Street was the Illustrated Daily News, a tabloid run by tall, aristocratic Manchester Boddy. He had been an enterprising salesman who, using hastily borrowed money, bought the bankrupt paper from young Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr. in 1926. Gradually, he turned it into a success — by adopting progressive causes and fighting against what seemed to be L. A. County’s pervasive graft and vice.

Brick Garrigues, eleven years Boddy’s junior, had left the Express copy desk to become one of the Daily News’ star reporters. His specialty was reporting on local politics — and bashing the city’s power structure.

There was plenty to bash.

•