Abridged from Why Didn’t Somebody Tell Somebody?, a pamphlet published by Los Angeles newspaperman Charles Harris (Brick) Garrigues in May 1938 and republished in January 1939. This excerpt is not included in the print version of He Usually Lived With a Female.

The illustrations are from the Los Angeles Public Library.

The Santa Barbara earthquake of 1925 lasted forty seconds. the Los Angeles quake of 1933 lasted about eighty seconds. The Saint Francis Dam disaster was over in seven hours. The Santa Monica Bay disaster has lasted twenty years and will last another twenty unless steps are taken to stop it.

Sand is an interesting thing. Each week between May and September approximately a million residents of Los Angeles County drive or ride from five to fifty miles to spend an hour or two or three lying upon it or in the water. Nobody ever thinks of where it came from or where it is going. It is just there. And then some season they find that their favorite beach is gone.

In the mountains and steep cliffs to the north of Santa Monica Bay the sand is made. Each winter, tons of it are carried down from the canyons between Topanga and Point Mugu. Day after day, night after night, the waves shift the sand southward, an inch at a time, past Santa Monica, past Ocean Park, past Venice, Del Rey, the South Bay Cities, until it is dragged into a huge subterranean chasm off the coast at Redondo.

Watch the waves rolling in, at a forty-five degree angle, but they roll out perpendicularly. As a wave strikes the beach, it stirs up the sand, holding it for a few minutes in suspension. During those few seconds, the entire mass of water has moved an inch or two southward; when the sand is deposited again, it has moved infinitesimally down the coast.

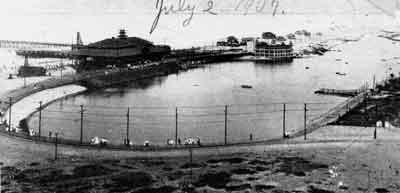

Not many remember the magnificence of the Playa Del Rey of thirty years ago — the pavilion built on the sea, the long, broad lagoon, protected by locks, where the “smart set” of the day came (driving down in carriages) for boating, canoeing and swimming.

That pavilion, with its piling and its jetties, started the destruction of the Del Rey beach. For the piers created a “dead area” in the surf — an area the waves did not empty. And so the sand began to pile up north of the pier, and the beach to the south began to suffer a “sand famine” as its own supply was swept southward.

Not many, for that matter, remember the Venice of a few years later — the model city of the day, laid out by that strange old romantic realist, Abbot Kinney, in an attempt to incorporate into one American town the best, the most colorful, the most glamorous — and perhaps the worst — of half a dozen of the most colorful cities of the New World.

Upon the completion of Venice, something happened to the Venice beach, exactly the same thing that had happened in Playa Del Rey: The construction of the Kinney pier and breakwater cut off the supply of sand south of the pier. For two miles, waves gouged at the narrow sand bar which is the city of Venice, biting further and further inland.

In 1916 the first disaster came. Twenty-eight houses were swept into the sea. Thousands of feet of beach were destroyed. The physical disaster of Venice had begun — a disaster without loss of life but surely destroying a city.

For Venice is not built upon solid earth, but upon a sand bar. Let that bar be eaten away and the sea will sweep in, pouring into the lagoons and canals below sea level and backing up the swamps half a dozen miles toward Culver City.

In 1933 another major step in the tragedy: Santa Monica built a yacht harbor. A long breakwater was thrown into the sea three miles north of Venice. A new dead area was created at the Venice beach, a vast sand trap sufficient to hold all the sand moving down the coast for fifty years to come.

Such is the slow destruction of Venice. About Venice future generations will not ask “Why didn’t somebody tell somebody?” but “Why didn’t somebody do something?”

And the answer to that, of course, is Greed.

If Venice had been a wealthy city like Santa Monica, it is probable that somebody might have done something. But the mistake of Abbot Kinney, the failure to foresee the effects of the automobile, took its toll. Cut off from the rest of the world, with no better highway than a twenty-foot alley, Venice became a city of Poverty.

Unlike Santa Monica or Santa Barbara, it did not have scores of wealthy influential citizens ready to battle for its future. The hundreds of thousands who came weekly to bathe on its beach did not live in or own property there. And so Venice slipped backward while its people vainly attempted to find some way of blasting a road through the city.

Here, too, they were defeated by Greed. But it was their own, dog-in-the-manger sort of Greed.

Everybody was agreed it should be built on one of three routes:

- Along the Trolleyway where the interurban railway ran.

- Along the narrow alley (known with official humor as the “Speedway”).

- Or in the middle of the block between the two.

The problem was that from 415 to 432 parcels of private property would have to be condemned — and paid for — if one of these routes were chosen.

The city and the county of Los Angeles joined to study the problem. The federal government weighed in. They came up with an answer:

- Run the road right down the ocean front, along public property.

- Between Santa Monica and Del Rey, build a series of groynes (narrow, semi-submerged piers) into the sea, to prevent the sand from being washed away.

- From the dunes south of Del Rey, where Uncle Sam was dumping four million cubic yards of sand into the sea to construct a sewage treatment plant, pump enough sand to fill out Venice Beach to the desired width.

The entire project could be completed by this method for two million dollars less than it would cost to get a highway, plus beach protection, by any other route.

The money was provided in the county budget. And then, from a new quarter, there bobbed up our old friend, Greed.

The years had brought to Venice a different atmosphere. Sideshows and ten-cent amusements had given way to a new industry — the tango business. (Tango is one of those amusements on the borderline of the law — sometimes legal, sometimes illegal, depending on the interpretation of the statutes. )

Into the plan to protect Venice was injected a war between those who controlled Venice — the tango operators — and the heirs of Abbot Kinney.

The Los Angeles City playground department wanted the site of the Venice pier for a major recreational area, with baths, solariums and concert halls. The Abbot Kinney Company wanted to sell to the city.

But that would have meant the destruction of the tango kings determined to keep their pier.

John Harrah, former mayor of Venice when it was an independent city, was one of the top tango operators. He knew how public officials can be controlled. He knew that Supervisor John Anson Ford, a bitter foe of the tango kings, couldn’t be touched by threats or promises. But he had a plan.

Very quietly he retained an attorney named Gilchrist who happened to be a relative by marriage of District Attorney Buron Fitts. Harrah promised him a fee of ten thousand dollars if he succeeded in blocking the program.

And so —

The county grand jury, always under the influence of the district attorney, suddenly announced an investigation of the proposed sale.

But it was never begun. It didn’t need to be. The announcement alone was enough to convince Supervisor Ford that something was wrong. He announced that he would oppose the entire program and indicated that anybody voting for it was probably working for the “corrupt interests which control Venice.”

His announcement was enough to swing Supervisor Herbert C. Legg also into the opposition. Legg was running for governor and could not afford to take a chance.

Supervisor Gordon McDonough, who gets the jitters every time the grand jury is mentioned, slipped out of town on one of his junkets just before the purchase was to be consummated.

The pier purchase was permitted to die — and with it there died the whole Venice protection program.

It was not until several months later that the real method by which the tango business was perpetuated began to come into the open.

For Harrah refused to pay Gilchrist his promised fee. Gilchrist went to court and sued the tango king. Harrah based his defense on the claim that the fee was to have been for the improper “influencing” of public officials and was consequently illegal.

The case is still being fought in the courts, and the testimony is revealing the whole story of how Greed blocked the protection of Venice.

And the Vanishing of Venice continues. Only when it is too late will the cry go up: “Why didn’t somebody tell somebody?”