By the end of the 1950s, my father, Brick Garrigues, had become the jazz reviewer for the San Francisco Examiner.

In those years San Francisco and Los Angeles were centers of a new kind of music — West Coast jazz, and in the San Francisco Bay Area young musicians were studying at academic institutions like Mills College in Oakland (under Darius Milhaud) and at San Francisco State College (where artists such as Paul Desmond, Cal Tjader and Pete Rugulo were just starting out).

In pop, Johnny Mathis had given up setting high-jump records at San Francisco State and was beginning his “Wonderful, Wonderful” career. The jazz establishment as

well came to San Francisco: Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars at Easy Street on Powell, for example, and June Christy at Fack’s on Bush Street.

C. H. Garrigues: jazz reviewer for the San Francisco Examiner. An acquaintance of musicians with a weekly column and a recognized name. Entrée to clubs and concerts. The ability to write about music and the capacity to do it with authority and style. No publishers or editors to say “Not this time!” It was almost like the 1920s, but with jazz, not opera, as Brick’s ticket to an arcane world.

Another difference from the Twenties: The young woman whom Brick occasionally took to hear the music was not a girlfriend but his teen-age daughter, my little sister, Patricia Garrigues.

Years later, Patty wrote:

Yes, the highlight of my teen life was going with Brick to the Blackhawk and other jazz clubs. It was fun; I felt like a grown up! I was probably about twelve or thirteen, though — any older and I may not have thought it was cool.

I remember going to the Monterey Jazz Festival with Brick and Naomi one year, and we sat near the front row because he had a press pass. It was great.

We saw Louis Armstrong, and he was wonderful. I was entranced with how much he perspired, and I counted the large handkerchiefs he used during his set — thirteen!

Never forgot that! Felt proud to be with Brick!

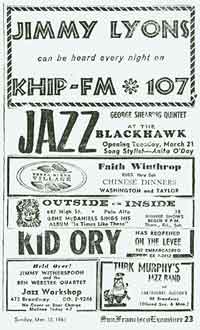

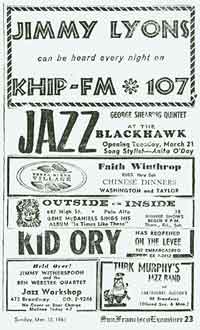

| San Francisco Examiner, March 12, 1961

A New Jazz Label

Voices a Shocking

Call for Freedom

By C. H. Garrigues

It is a remarkable fact that jazz, though it has grown up in the veritable shadow of social injustice, has had almost nothing to say about the grave blot on our social structure which has made most jazzmen second-class citizens and, in some section of the Nation, deprived them even of the right to be human beings.

Aside from Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” there is virtually nothing in the experience of jazz to make one aware that most jazz musicians are Negroes. Nearly a century after the Emancipation, these people still find themselves treated with contempt in almost any town or hamlet in the land, solely on the basis of their race.

True, in recent years a few jazzmen have become somewhat more daring. One went so far as to honor a new African nation by giving its name — spelled backward — to one of his tunes. [Sonny Rollins with his “Airegin.”]

And it is a more or less open secret in the jazz world that all the furor about “soul” is code for “the brotherhood of Negroes for Negroes.” And “soul music” is a musical assertion of the validity of the Negro’s social, cultural and musical heritage.

It is against this somewhat negative background that Candid Records — a new jazz label but already a major force in the jazz world — has issued “We Insist — Max Roach’s Freedom Suite” (Candid 8002).

It is an album which may prove to be the most controversial jazz album ever issued.

It starts rationally enough with “Driva Man,” a musical reminder of the days of slavery with Abbey Lincoln singing the bitter lyrics in front of Coleman Hawkins, Walter Benton, Julian Priester, James Schenck and Max Roach. Then “Freedom Day” expresses the joy which was to have come (reminding one at the same time vaguely of Ellington’s “Emancipation Proclamation”).

A triptych opens not surprisingly with “Prayer.” And then, without warning, one is thrown into “Protest.” — an experience somewhat comparable to that of strolling on a lovely afternoon through a peaceful Southern wood to come upon a lynching, the victim’s feet still kicking gently, his slayers vanished.

Miss Lincoln’s performance will be attacked upon both esthetic and social grounds.

It will be said that she does not sing but screams — and that is true.

It will be said that the function of art is, as Aristotle saw it, “by imitation, to purge the soul of pity and terror,” not to make you want to run home and hide your pale-faced head in terror and shame.

But two other things must also be said:

That having heard Miss Lincoln singing on this record, you will never forget it.

And that if even a moderate portion of Americans today feel the outrage Miss Lincoln expresses toward the actions of other Americans, then this Nation had very well look to itself, for it will not be Russia which will destroy it.

|